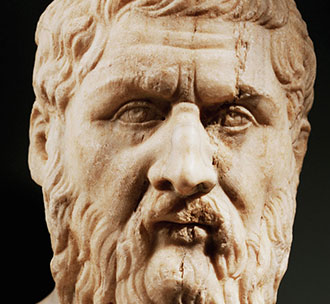

What was play in the classical period? How did Plato view play?

Armand D’Angour, Faculty of Classics at Jesus College, Oxford University, provides answers to these questions in his informative and accessible writing in “Plato and Play”. He states,

The relationship of the word paizein, play, to pais, child, may suggest that for Greeks “play” referred intrinsically to activities relating to children rather than to adults. However, the term naturally extends to activities we might not view as laborious, serious, or solemn. Ancient Greek texts mainly construe “play” as the opposite of “work,” or exertion, which in the mainly agrarian context of Greek life had connotations of agricultural labor. More generally, play related to a range of pursuits involving paignia, toys or trifles, in both a literal and a figurative sense. But, just as we say that we “play” music and sports, the Greeks naturally referred to these activities as paizein. The Greeks did not particularly associate these forms of play with children, nor did they think of them as trifling. Whether music accompanied religious ritual or glorified athletics in the Olympic games, Greek society took it no less seriously than does ours. (Spring, 2013, p. 295)

The Greeks view of play etymologically might appear to be child’s play from the words “paizein, play, to pais, child” (D’Angour, 2013). But D’Angour cautions us to not limit our understanding of classical period’s view of play to etymology. As he details:

“in the classical period (fifth and fourth centuries BCE), the referents of “play” embrace ubiquitous expressions of music and dance, competitions both sporting or artistic, and the lively pursuit of abstruse forms of knowledge associated with the Sophists (professional teachers). We should not, therefore, be misled by etymology into thinking that ancient Greeks constructed all play as merely child’s play.” (p. 295)

Reflecting on Plato’s contribution to play he states,

The real target of Plato’s concern, however, was neither children nor toy makers, but the society of his time. Politics in Athens during and following the Peloponnesian War (fought between 431 and 404 BCE) were beset by infighting between political groupings led by upper-class young men, demonstrating the changeability and inconsistency of an imperfectly functioning radical democracy. It was Plato’s genuine contribution to ask what had led to such a fluid and dangerous political landscape and to conclude that children habituated to change in their early lives might grow into restless and dissatisfied adults. (p. 301)

This raises for me the question of what was Plato’s view of change? What is change? I believe change is constant. And that change comes in many forms. Childhood is a period when one can see constant growth in a child and thus change. But that doesn’t lead me to think of change as constant. Rather it is the view that we are always making meaning and creating who we are that positions us changelings and as change makers.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks